In exile, Chechen women play a central role in preserving and transmitting their cultural heritage while also navigating transformation. They safeguard traditions by teaching the Chechen language, passing down traditional dance, and maintaining ancestral recipes. At the same time, exile offers a space for them to reinterpret their roles within the community. Some fully integrate into their host society, pursuing higher education and professional careers. Others embrace traditional gender norms, marrying young and focusing on family life, viewing the transmission of Chechen values and language to their children as their contribution to cultural preservation. Exile, therefore, is both a site of preservation and transformation, where cultural identity is upheld, adapted, and negotiated.

The journey of the Chechen diaspora in Europe

The Chechen diaspora in Europe began to take shape in the early 2000sExternal link. Initially, refugees fled a devastating war, only to later escape the repression of Ramzan Kadyrov’sExternal link authoritarian regime. From exile, they remain distant witnesses to the regime’s violence and actively reject the official memory it seeks to impose. Instead, they construct new, plural identities and narrativesExternal link, shaped by both a romanticized vision of their homeland and vivid recollections of a recent, brutal conflict.

Over the years, the Chechen diaspora in Europe has gradually organized itself, establishing solidarity networks to support new refugees. Numerous cultural associationsExternal link and human rights organizations advocating for Chechens have emerged in cities such as Paris, Nice, and Vienna, providing assistance, fostering community ties, and ensuring the preservation of Chechen heritage in exile. As the second generation of Chechens—those born in Chechnya but raised in Europe from a young age—came of age, they faced the challenge of navigating a dual cultural identity. Having completed their education in their host countries, they had to find ways to preserve and promote their Chechen heritage while fully integrating into European society. This delicate balance required them to engage in cultural initiatives, language preservation efforts, and artistic expressions that allowed them to maintain a connection to their roots while embracing the realities of their new home.

Promoting visual arts

Logo of the VART collective

Image: @vaynakhartVisual arts, such as photography and painting, have become powerful media through which women in the diaspora ensure cultural transmission. By reclaiming these artistic forms, they not only preserve their heritage, but also create new spaces for dialogue, expression, and resistance. In this context, the VART collectiveExternal link stands as a significant initiative, allowing artists to claim their Chechen heritage in public and international artistic spaces. According to Amina, its founder, VART is a collective of artists from the Caucasus, specifically Chechen and Ingush artists. It brings together contemporary VainakhExternal link artists, providing them with a platform to connect and showcase their work.

For me, it is important to continue speaking about this heritage, which is rich in culture and history. It is both evident and essential to preserve these values that our ancestors passed down and to put them into practice even today.

Amina, founder of VART collective

Image by @assoueva

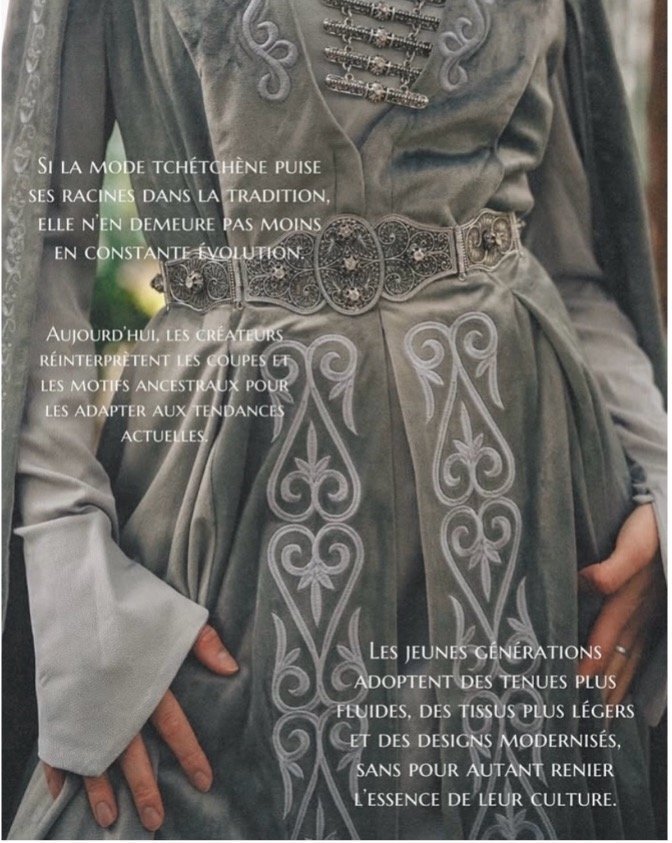

Image: Fatima Assoueva @assouevaWhile Chechen fashion draws its roots from tradition, it remains in constant evolution. Today, designers reinterpret ancestral cuts and motifs to adapt them to current trends. Younger generations are adopting more fluid outfits, lighter fabrics, and modernized designs, without renouncing the essence of their culture.

Amina, founder of VART collective

Dancing the Caucasus

Dagmara[1] is a 21-year-old Caucasian dance instructor based in Nice, France, a city home to a significant Chechen community. She’s deeply passionate about Caucasian dance. She seeks to convey the essence of the Caucasus to her students through her teaching. Beyond the technical aspects of dance, she also imparts knowledge about its cultural and historical significance. To support language preservation, she communicates with her Chechen students in Chechen, encouraging them to practice and maintain their linguistic heritage. Dagmara has faced criticism on social media for making her classes accessible to non-Chechens and for performing dances from other Caucasian traditions, such as Avar and Georgian dances. She interprets these reactions as a reflection of a broader social issue—an unwillingness to engage in cultural exchange—rather than a legitimate concern. She firmly believes that sharing one’s cultural heritage enriches both the community and those outside it.

Dagmara states that while exile has given her opportunities, such as the chance to study at university and aspire to become a teacher, it has also allowed her to gradually challenge the deeply ingrained gender norms of Chechen society. She grew up in a family where she’s the only girl among brothers, and her mother raised her to serve them and the men in her family. Over time, this situation became unsustainable, as her academic work began to suffer due to the burden of household responsibilities. Gradually, despite resistance from the elders, she managed to involve her brothers in daily household tasks, something she describes as “unimaginable in Chechnya.”

Content creation and cooking

This questioning of gender roles is not unanimous within the diaspora, as some women see it as a way to serve and care for those they love. Asya is a Chechen content creator living in Belgium. Her content is diverse, but primarily revolves around cooking. Through her “Traditionnelle” (meaning “traditional” in French) series, she presents Chechen dishes from her childhood and explains her recipes in French. She states that the purpose of speaking French in these videos is to help Chechens in the diaspora who have not had the opportunity to grow up immersed in their culture to learn more about it, while also introducing foreigners to Chechnya through its cuisine. Asya does not show her face on social media, and when I ask her about this choice, she mentions cultural reasons, but primarily emphasizes religious ones. Asya accepts certain cultural norms imposed on women, such as the prohibition against wearing trousers or traveling alone. From her perspective, these practices align with religious teachings she’s attached to.

Screenshot from episode 5 of the “Traditionnelle” series

Image: @_askitommBetween Custom and Conviction: Chechen Women’s Religious Transformation in Exile

For many Chechens who have fled war and repression, exile is also an opportunity to experience freedoms that were previously denied to them. Among these freedoms, the right to religious expression stands out as particularly significant. While the Chechen Republic under Ramzan Kadyrov imposes strict controlExternal link over religious practices—often suppressing interpretations of Islam that do not align with the state’s vision—exile offers a space where faith can be practiced without fear of persecution. One of the most visible expressions of this newfound religious freedom among Chechen women is the choice to wear the jilbab, a long, loose garment often associated with Salafi interpretations of Islam. In Chechnya, such attire can lead to suspicion of extremist affiliations and even arrest.

Many of these women living in the diaspora and wearing jilbab adhere to a strict interpretation of Sunni orthodoxy. Although they remain deeply attached to their Chechen identity, they prioritize religious doctrine over cultural traditions. For them, faith transcends national customs, and they reject elements of Chechen culture that they view as incompatible with Islamic teachings. This can lead to tensions within the diaspora, as traditional Chechen norms sometimes clash with strict religious interpretations. When I ask Aminat, a 22-year-old master’s student in France, about the role of music and lovzar (traditional Chechen dance performances) in weddings, she explains that she does not personally embrace these customs. While she recognizes them as part of Chechen culture, she could not include anything in her own wedding that contradicts her religious beliefs.

Aicha and Fatima, both 20 years old and raised in a family that follows Salafism, share a similar perspective. They dream of a small, intimate wedding without music or dancing, in accordance with their religious convictions. One of them even envisions wearing the niqab—a full-face veil—on her wedding day, reflecting her commitment to a strict interpretation of Islamic modesty. As a result, Chechen weddings in Europe have become increasingly diverse, with no two weddings looking exactly alike. Some weddings within the Chechen diaspora are now gender-segregated, featuring no music or dancing. In certain cases, out of religious modesty, the bride does not even appear in the main reception hall.

This phenomenon highlights the complex interplay between religion, culture, and identity in the Chechen diaspora. While exile offers a space for cultural preservation, it also allows individuals to redefine their values and beliefs on their own terms.

[1] The name is a pseudonym.

Author bio: Loujaine Laamal is a PhD candidate in political science at the Université libre de Bruxelles (ULB), funded by the FNRS. Her research focuses on the Chechen diaspora in Europe, exploring the construction of its identities and its political opposition movements.

Peer reviewed by: Prof. Dr. Diana Forker, Project Leader and Co-Principal Investigator, Institute for Caucasus Studies, Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena