07/04/2025

Civil society in Georgia has long been praised as vibrant and dynamic, but now it faces the challenge of proving its resilience during difficult times. The dynamism in the past was largely fostered by the country's modern political transformation, which allowed space for Civil Society Organizations (CSOs), media, and grassroots movements to flourish. Several factors contributed to this environment: a favorable legal framework for the registration and operation of CSOs and other forms of civil society, unrestricted access to domestic and international funding, relative observance of civic rights by the authorities, and the government’s declared commitment to engaging in policy dialogue with civil society at all levels of governance.[i] This dynamic was reflected in the Civil Society Sustainability Index, where Georgia consistently maintained the status of “evolving”.

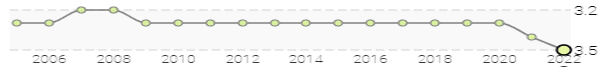

Graph 1. Georgia - Civil Society Sustainability Overall Index

Image: David AprasidzeSource: https://csosi.org/External link (value 7-1, lower score indicates more sustainable; 5-3 denotes “evolving”)

Despite this progress, several constraints limited the further development of civil society. These included financial dependence on international (mainly European and U.S.) donors and a scarcity of local funding, a lack of broad civic participation and public recognition, and visible participation in but limited impact on public policy. Yet, despite these, the legal environment was historically rated as the best-performing indicator compared to others like organizational capacity, financial viability, advocacy, service provision, sectoral infrastructure, and public image.

Graph 2. Georgia - Civil Society Legal Environment Index

Image: David AprasidzeSource: https://csosi.org/External link (value 7-1, lower score indicates more sustainable; 5-3 denotes “evolving”)

DETERIORATION

The situation began to change in December 2022 when the ruling Georgian Dream (GD) party and its satellite People Power initiated the Law on Foreign TransparencyExternal link. The law sought to establish a registry of civil society and media organizations receiving more than 20% of their funding from abroad. However, alarming signs of deteriorating state-civil society relations had already become evident. Representatives of GD and the government frequently launched verbal attacksExternal link on civil society actors and independent media. Georgia has witnessed strained state-civil society relations before, such as prior to the Rose Revolution in 2003 and during the 2012 election campaign, which marked the first (and so far, only) transfer of power through elections in Georgia. However, until 2022, these tensions never translated into legal restrictions. Even in 2023, after appeals from international partners and widespread domestic protests, GD withdrew the proposed legislation.

The red line was crossed in 2024 with the reintroduction and ultimate adoption of the lawExternal link, now titled The Law on Organizations Pursuing the Interests of a Foreign Power. Despite large-scale protests and clear warnings from Western partners about the law’s negative implications for Georgia’s European and Euro-Atlantic aspirations, GD proceeded with its passage. Accompanied by blatant anti-Western rhetoric and propaganda, the government portrayed Western-funded civil society as "foreign agents" and enemies of the stateExternal link.

The new law requires CSOs receiving more than 20% of their funding from foreign sources to register and submit annual financial declarations. Proponents claim the law aligns with Western democratic standards, but similar legislation is commonly used to suppress civil society in authoritarian states, particularly Russia.

INITIAL REACTIONS

Civil society did not develop a comprehensive strategy to adapt to the new reality after the adoption. Despite numerous statementsExternal link from CSOs, business associations, trade unions, and other actors, as well as analytical and legal reviews produced both domestically and internationally, the initial focus was on preventing the law’s passage. Once the law was adopted, civil society shifted its efforts toward a second objective: mobilizing for the general elections in October 2026. This included active engagement in election observation, exemplified by the creation of the observation coalition "My Vote,"External link founded by several CSOs and activists. The hope was that the elections would lead to a change in government, and that the new authorities would repeal the legislation.

At the tactical level, several options were considered by the civil society community. Some organizations, primarily capital-based, attempted to establish entities abroad, particularly in Eastern Europe, to circumvent the obligation to register, as the law in its current form does not apply to foreign non-profit entities or their representations. Other organizations opted to create new entities, thereby postponing the registration requirement until January 2025. However, these measures did not exempt pre-existing organizations from the obligation to register, even if they had effectively ceased operations. Moreover, establishing entities abroad was less feasible for smaller or less experienced organizations, especially those located outside the capital.

The majority of CSOs were not planning to register before the elections. A survey conducted between July and September 2024External link revealed that only 6% of organizations were ready to register, while 75% had no plans to do so, and 19% remained undecided. By the end of 2024, the registry included 385 entries. While this is not an insignificant figure compared to the estimated total number of 1,285 active CSOs according to the most comprehensive CSO databaseExternal link,[i] a closer examination of the registry showsExternal link that none of the leading organizations are among those listed.

WHAT NEXT?

The situation in Georgia continues to deteriorate. Despite the Georgian Dream-controlled parliament lacking both domestic and external legitimacy and ongoing public protests, the government persists in adopting restrictive lawsExternal link that further erode civic liberties, including the rights to freedom of assembly and expression. Dozens of protesters have been arrestedExternal link on administrative charges, while several have been imprisoned on criminal charges.

In February 2025, USAID - one of the largest donors to civil society in Georgia - ceased its operationsExternal link, stripping many CSOs across the country of crucial core funding. Although the EU and some of its member states have pledged to support civil society by redirecting funds from public institutionsExternal link to the non-governmental sector, fully compensating for the lost funding remains a significant challenge.

Moreover, in early March 2025, parliament passed the Foreign Agents Registration ActExternal link (FARA) in its first reading. This new law is set to replace the existing legislation and impose even stricter controls on civil society, independent media, and civic activists, including introducing criminal liability for failing to comply with its provisions.

It is becoming increasingly clear that, at least in the short term, the future of Georgia’s civil society depends entirely on the political will and calculations of Georgian Dream. The enabling environment that civil society has enjoyed since the mid-1990s is effectively coming to an end. Under the current government, a return to previous levels of state–civil society relations appears highly unlikely. Having operated in a relatively favorable environment for decades, civil society now faces a far more unpredictable and hostile landscape. In other words, its capacity for resilience is being pushed to the limit.

Author Bio: David Aprasidze is a professor of Political Science at Ilia State University in Tbilisi, Georgia. His academic interests include political transformation, democratization, and Europeanization in the EU neighborhood. In the summer of 2024, he was a Jena-Cauc Fellow.

Peer reviewed by: Prof. Dr. Kornely Kakachia, Director of the Georgian Institute of Politics, Professor of Political Science and Jean Monnet Chair at Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University, Georgia.

[i] According to the national legal entity registryExternal link, there are more than 33,000 non-for-profit organizations in Georgia. However, many of these organizations are either dysfunctional or have been established by public agencies.

[i] The CSOs were part of the Open Government Partnership Initiative (OGP); the Memorandum of Understanding between the Parliament of Georgia and the Georgian National Platform of the Civil Society Forum of the EaP was in force; Civil society representatives were included in numerous public councils and cross-sector working groups; Local Action Groups (LAG) in 8 municipalities were created with participation of civil society and local authorities.